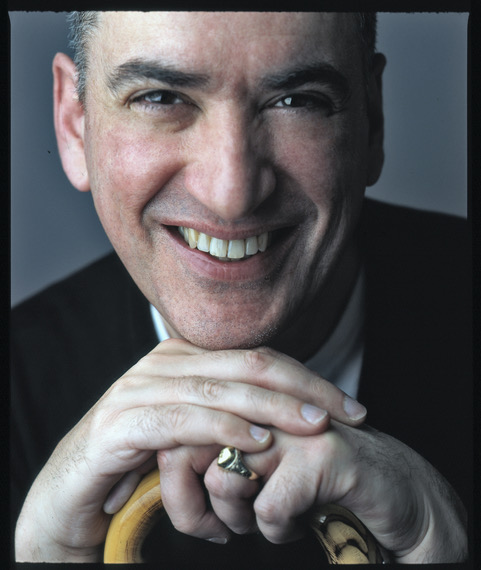

Vancouver, Canada’s John Lekich is a journalist, essayist and the author of several books for young adult readers. They include the novels The Prisoner of Snowflake Falls, King of the Lost and Found and The Losers’ Club. His most recent YA novel is Murder at the Hotel Hopeless (Orca Books 2022).

His YA novels have received critical acclaim from various publications, along with recognition from such organizations as The Young Adult Library Services Association, The Canadian Library Association and The Detroit Public Library. His debut YA novel, The Losers’ Club, was a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award.

Born with cerebral palsy and the youngest of six kids, he spent a lot of his childhood reading books on a wide variety of subjects. When he was 14, his older brother Bill suggested he read a novel by Mark Harris called Bang the Drum Slowly. The book inspired him to become a writer.

As a child in Vancouver, John also developed a passion for old movies, and by high school became interested in writing and directing for the stage. His first play was produced the year after he graduated from high school.

While working towards a Bachelor of Education at the University of British Columbia, John discovered a talent for journalism and writing movie reviews. After two years teaching English and drama at a local junior high, he turned to freelancing for newspapers and magazines, winning numerous awards and eventually becoming the first West Coast film correspondent for The Globe and Mail, Canada’s national newspaper.

His articles, reviews and essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Reader’s Digest, the Hollywood Reporter and Vancouver’s Georgia Straight. Some of his favourite interviews include actor Audrey Hepburn, comedian Steve Martin and silent screen legend Lillian Gish.

He is currently working on an idea for a new YA murder mystery.

Q: Your young adult novels are consistently reviewed as having “humor and heart,” and your characters as “feisty.” Do those three characteristics describe you as well, and if so, what in your background most contributed to those qualities?

A: I grew up as the youngest of six kids in a very loving family. So there was a lot of laughter around the dinner table. I think when you grow up in a family with older brothers and sisters, it encourages a lot of things that come in handy later in life. You learn certain things early – kindness, consideration, compromise. And a way to evaluate and understand other points of view.

That’s what our parents did for all of their children. And it’s their legacy because we’re all still very close to this day. We support each other. If there’s any heart in my writing, it started with what my parents taught me. They really believed in kindness and empathy. And they practiced it in daily life.

My father ran a diner and he liked to say that nobody ever left his place hungry – whether they could pay for a meal or not. When you’re a kid, that kind of stuff really sticks with you.

I don’t know if I would describe myself as feisty. I suppose it would be fair to call me resilient. Being born with cerebral palsy made me focus on the things I needed to do, despite the obstacles. When you fall down, you get up and get on with life. That was an important lesson early on. And I had a lot of help from family that way. Especially from my twin sister, who went through school with me. And was always there to help out.

Q: How does your passion for film and screenwriting affect your approach to fiction?

A: I grew up watching a lot of old black and white movies on TV. And probably way too much television. As a novelist, I think watching so many classic films – along with some of my early attempts at screenwriting – helped me to develop a sound ear for dialogue and pace. My lifelong love of movies and TV is just part of my creative DNA.

All of my novels include references to TV shows, commercials or classic movies. The protagonist in King of the Lost and Found, for example, likes to watch reruns of Julia Child’s The French Chef – which I used to do with my mother. And – like me – the protagonist in my novel The Losers’ Club loves The Marx Brothers.

I had great fun coming up with the TV references in Murder at the Hotel

Hopeless – which features Penny Price, the star of a fictional TV detective series called Little Miss Murder.

In a way, Murder at the Hotel Hopeless is a kind of affectionate tribute to those classic black and white murder mysteries I loved to watch growing up. Stuff like The Thin Man movies – that wonderful series with William Powell and Myrna Loy – which moves at a very brisk pace and is driven by quick, punchy dialogue. Along with that feeling of betrayal and suspense that’s so vital to any murder mystery, all those classic movies managed to weave in a lot of subtext about loyalty and the true meaning of friendship.

I wanted Murder at the Hotel Hopeless to contain all those elements. Although the story is very contemporary, the plot moves extremely fast and showcases a lot of the characteristics of the classic murder mystery.

Q: So far, all your young adult novels have featured male protagonists. Is that what you’re most comfortable with, or are you aware there’s a lack of books with male main characters out there — or are there other reasons you tend toward fun, heroic male leads?

A: All my novels feature bright, resourceful female characters and often draw on my experience growing up with four sisters. That said, I think my novels feature male protagonists because – even after all these years – I still feel most secure drawing on my own personal experiences growing up. This always provides a solid emotional foundation so that I can confidently build on the main male character from the ground up. After that, I can go wherever my imagination takes me.

For example, the male protagonist in my novel The Prisoner of Snowflake Falls is an accomplished teenaged burglar forced to steal to survive. The plot is about as far from my own childhood as I could get. But I still had the security of knowing that I could relate to certain universal feelings that all teenaged boys go through. Feelings that I remember experiencing as a guy growing up. And that I can still get in touch with through writing.

Q: Growing up with cerebral palsy, did you ever reflect on a lack of characters with disabilities in the books you read? Did that in any way instill a desire to redress that in your work? Several of your books have included characters with disabilities, even a fleeting reference to a potential suspect in a wheelchair in Murder at the Hotel Hopeless, perhaps implying you’re aware that such individuals can be all too invisible. (Your adult biography, Plan B: One Man’s Journey from Tragedy to Triumph, also implies a passion for putting such experience out there.)

A: When I wrote The Losers’ Club – almost 25 years ago now – it may have been a bit more unusual to focus on a main character with a lifelong disability. At the time, I didn’t think I was doing anything particularly groundbreaking. Since it was my first YA novel, I simply wanted to draw on something I knew intimately. But I’ve always been gratified by the strong positive response.

As a novelist, I became interested in exploring other forms of emotional and physical challenges. As a writer, I’ve always been attracted to the way people face such challenges, especially ones that are unforeseen. So it was a privilege to co-author former BC premier Mike Harcourt’s Plan B: One Man’s Journey from Tragedy to Triumph, which tells the true story of his inspiring recovery from a life-changing injury.

I also think that because of Mike’s story and others over the past couple of decades – along with some encouraging social changes over the years – the average person has a greater understanding of what it might be like to live with a disability. Since I was a kid – which is a long time ago now – things have begun to change for the better in many ways.

It’s no accident that there’s a brief reference to a character in a wheelchair in Murder at the Hotel Hopeless. Just as it’s no accident that one of the pivotal characters in the novel walks with the aid of a cane. Since the backdrop of the story takes place in a hotel, I wanted the tenants to reflect the mix of a real and true community. And part of that true mix is acknowledging that every community features people with disabilities as a vital part of daily life.

Q: You’ve written everything from newspaper film reviews and screenplays to adult nonfiction. What’s the special draw of writing young adult fiction?

A: I fell into writing YA fiction purely by accident. A publisher approached me with an idea of writing a non-fiction YA book. At the time, I was well into attempting my first novel and was discovering how much I enjoyed the experience. So I asked them if I could pitch an idea for a YA novel. And that became The Losers’ Club.

After that, I continued to explore other genres. But I kept coming back to YA novels for a number of reasons. Young adulthood is a time of life where there’s so many changes and challenges, which makes for a very rich sense of storytelling. The process of growing up – of struggling to become a fully aware person – always offers a writer so many interesting options because there’s so much scope emotionally.

The YA genre also offers the opportunity to explore the relationship between young adults and their parents, guardians or teachers. In all my novels, the adults are often struggling to understand life in a way that mirrors the experience of the younger characters. And I’ve always been proud of portraying that kind of shared complexity. Because I don’t think there’s any magic age where life necessarily becomes easy. Adulthood has its difficulties too. We’re all just doing the best we can to figure out life.

Q: Can you talk about the importance of weaving humor into stories for young adults, especially boys?

A: It’s just a theory. But I think boys tend to cope – or even mask – various difficulties in life through the use of humor. I know I did this a lot while growing up. And I wanted to portray that trait in my books. Also, I just really like making my readers laugh. And I enjoy making myself laugh while I’m writing. It just makes the process so much fun. For me – and most importantly – for the reader.

One of the great pleasures of my writing career is getting the occasional message from a reader – often a male reader – that will say something like: “I was having a terrible day but your book made me laugh out loud.” Things like that make all the work worth it.

In fact, without the humor, I’m not sure I would have been able to finish any of my novels. That’s because all of them have a deep underlying sense of loneliness and loss. And humor is a way to make some of those more somber aspects palpable.

Virtually all my characters are social outcasts in some way – doing the best they can to get through whatever setbacks life constantly offers. They have a rough time in various ways but they never lose their sense of humor for long. A dry sense of humor is one of life’s greatest tools for prevailing over sadness. In Murder at the Hotel Hopeless, for example, it’s part of a need to find a way to connect with others. To understand the true meaning of friendship and compassion. Even in the face of danger. Which – when all is said and done – may be the most heroic thing any of the characters do.

- Pam Withers