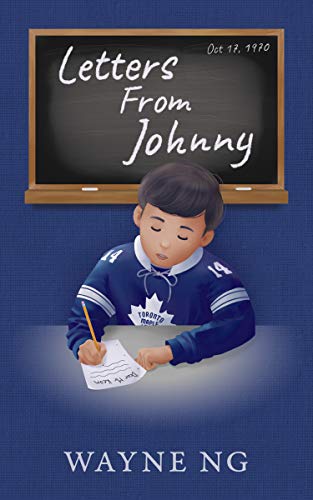

Letters From Johnny

Genre:

Author: Wayne Ng

Publisher: Guernica Editions

Set in Toronto 1970, just as the FLQ crisis emerges to shake an innocent country, eleven-year-old Johnny Wong uncovers an underbelly to his tight, downtown neighbourhood. He shares a room with his Chinese immigrant mother in a neighbourhood of American draft dodgers and new Canadians. In a span of a few weeks his world seesaws. He is befriended by Rollie, one of the draft dodgers who takes on a fatherly and writing mentor role. Johnny’s mother is threatened by the “children’s warfare society.” Meany Ming, one of the characters by the rooming house is found murdered. He suspects the feline loving neighbour, the Catwoman. Inspired by an episode of Mannix, he tries to break into her house. Ultimately he is betrayed but he must act to save his family. He discovers a distant kinship with Jean, the son of one of the hostages kidnapped by the FLQ who have sent Canada into a crisis.

left no-repeat;left top;; auto

I like this book. I didn’t think I would at first. The story is told by

Johnny through a series of letters assigned by his teacher, first to a pen

pal and later to hockey legend Dave Keon. As an eleven-year-old, Johnny’s

writing skills aren’t very well developed when the book opens, and all of

his errors are kept intact for readers. About his neighbour, Rollie, Johnny

writes, “He rents a room beside us except we have the biggest room in the

house and we share the washroom and the kitchen with him and two

younivercidy

univercidy students in the rooms down stairs.” As an English teacher, I had

to curb the desire to get my red pen out right then and there.

The run-on sentences, misspellings, lack of punctuation around dialogue, and awkward constructions slowed my reading at first; however, those errors also became part of the book’s charm. Johnny writes like an actual eleven-year-old. Before long I found that I had grown accustomed to his style, and that he had a recognizable voice. And, of course, Johnny’s writing improves. Like Flowers for Algernon, his language use becomes gradually clearer and more sophisticated as he writes, noting that even though Rollie hates writing, “He should try. It is not so hard.”

The book also doesn’t shy away from uncomfortable situations among its characters: Johnny’s mother’s alcoholism, his father’s extramarital relationship, his principal’s smoldering bigotry and his attempts to find his place in a Canada that sends mixed messages about belonging. Apprehended while slumbering in an Eaton’s store, Johnny is offered a Kit Kat bar by one of the employees: “[He] said it is no egg roll or chop suey but its good eh. I think he was trying to be nice and funny but it was not.” What we get from Johnny is a confusing jumble of complexities for a boy coming of age without the safety and guidance we all wish for our children. In other words, a real life.

Letters From Johnny is ideally suited for readers from ages eight to ten, though some older readers may be drawn in by their connection to Johnny’s family complications, their empathy for the struggles of first-generation Canadians or, as in my case, by their own sense of nostalgia for those halcyon, cellphone-free days.

- M.D.S.

left no-repeat;left top;; auto