Posted January 3, 2025

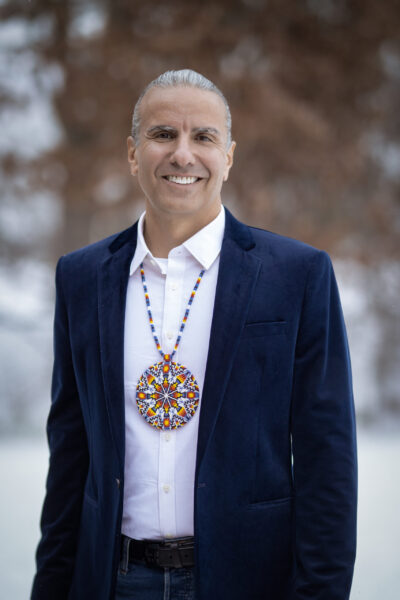

Anton Treuer of Bemidji, Minnesota is a professor of Ojibwe who has written or edited more than 20 nonfiction books for adults, emphasizing history and American Indian studies. These include Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians but Were Afraid to Ask and Atlas of Indian Nations. Now he has written a first novel, Where Wolves Don’t Die (Levine Querido 2024), “a taut thriller and a raw, tender coming-of-age story, about one Ojibwe boy learning to love himself through the love of his family around him.”

Anton has won more than 40 prestigious awards and fellowships, and can be found at https://antontreuer.com/ and @antontreuer.

Q: With your extensive academic background, and as an educator of adults with a special interest in history, what led you to write a contemporary novel aimed at teens? It seems a sharp and brave departure.

A: I have nine children and we have been launching a teenager every couple of years for the past decade. I think about parenting, coming of age, and the recent passing of my own parents often. I also teach our tribal language, Ojibwe, and officiate at many of our traditional ceremonies. My life has been filled with young people and elders and the rich tapestry of our ceremonial culture with one foot in the northwoods and another in my academic work. Writing Where Wolves Don’t Die didn’t require me to imagine Indigenous culture or Native places. It provided an opportunity for me to open a window for the reader to get an authentic view of our universe.

Q: You’ve said, “I want to turn Native fiction on its head. We have so many stories about trauma and tragedy with characters who lament the culture that they were always denied. I want to show how vibrant and alive our culture still is. I want gripping stories where none of the Native characters are drug addicts, rapists, abused or abusing others. I want to demonstrate the magnificence of our elders, the humor of our people and the power of forgiveness and reconciliation.”

This is a thriller featuring an aggressive bully with whom the main character has to deal. And it’s from the point of view of a 15-year-old Ojibwe boy. Of all the many plotlines and characters you could have created, why these elements and why a male protagonist?

A: Dealing with adversity and the tension between fitting in and standing out is something that all of us experience in coming of age. This is a human story that should relate to all humans. But it also happens in a specific cultural context. That will hopefully be relatable for Native readers and compelling for everyone else. I chose to write a male protagonist in part because I have five sons who have all become adults, going through their first kill ceremonies and navigating the transition and need for independence with their love of family and community and connection. But I also feel like the literary world has started to do better at holding up more work by female authors and authors of different gender identities. This is welcome but emerging work and we need much more of it. We have also started to identify some of the negative messaging about masculinity—toxic masculinity. But we haven’t done enough work to show what healthy, positive masculinity looks like—a boy dealing with life, and story full of tension, who finds his way to an awakening and healing transformation. I think Where Wolves Don’t Die says something important about that.

Q: Which aspects of Where Wolves Don’t Die stem from experiences in your life, if you’re willing to share that? For instance, the racist high school bully, Ezra’s grief at losing his mother, the way summer camp counsellors ignore the assault on Ezra, the crush on the powwow performer, urban discontent or parental relationships in general?

A: This is a work of fiction, but I did draw upon life experiences of my own. I went to a summer camp and experienced racial bullying and the failure of staff to intervene. I lost my mother, but as an adult rather than a teenager. I have also been parenting my own nine children through coming of age. I have two still at home and the rest have become adults. I have also spent a lot time with my elders, and the characters of Grandpa Liam and Grandma Emma feature prominently in the work.

Q: As a father who dedicated this novel to a son, can you talk about how having sons influenced you?

A: Being a parent is terrifying. The number one job is “do not mess your kids up.” But there is no way to save them from the world. They will likely find friends, fall in love and connect with their grandparents and you. All relationships are vulnerable. Someone always dies first. And sometimes there is a living death—when someone leaves or descends into darkness. We cannot shield them from pain without shielding them from love itself. But we can equip them with tools and perspective to navigate the pain and foster deep connection. I try to do that as a parent. In the book, Ezra is wrestling with that through his journey to a deep realization. I found writing this story very personal for these reasons.

Q: What do you hope a) Native and b) non-Native readers take from this novel? And are those hopes connected to your comment that this is “the best thing I’ve ever written”?

A: Everyone who lives into adulthood has a coming-of-age experience. That transcends our specific cultures. But coming of age, for all of us, happens in a specific cultural context. Colonization has centered the shared human experience of coming of age in white, Eurocentric cultural environments—British and American schools, towns, cities and cultures. The assumption has always been that literature which shares about white coming-of-age experiences shares about the HUMAN experience. And literature that shares about coming of age in other cultures shares about MINORITY experiences rather than the HUMAN experience. The assumption is Eurocentric. All coming-of-age literature says something about the human experience of coming of age; and it says something about the culture in which it happens. Where Wolves Don’t Die speaks to both our shared human experience which transcends all the lines and divisions between us—breaking from and maintaining connection to our families of origin, leaving and coming home, freedom and belonging. And it also provides a very distinctive and authentic cultural tapestry for the storytelling, one that will resonate with Indigenous readers and be novel to others. A great story will effectively transport the reader into the characters and culture of the book and transform the reader through the journey.

Q: Can we hope for subsequent young-adult novels?

A: : I have more books in my head than time! But you will see more fiction from me and other things too.

– Pam Withers