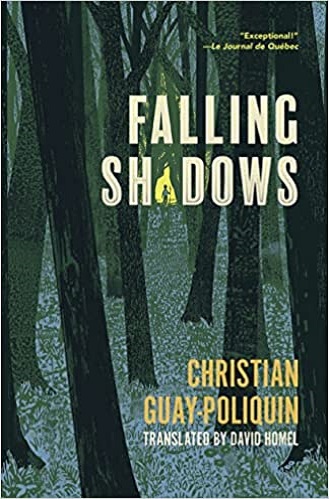

A lone man walks in the forest towards the hunting camp where his family has taken refuge to escape the upheaval caused by a widespread power failure. He knows he is threatened. One day, having lost his way, a twelve-year-old boy, mysteriously fearless and familiar, calls out to him. The unusual duo will have to face the hostility of the wilderness and thwart the offensive groups that now inhabit the woods.

A fascinating thing about dystopian novels is that authors often must work very hard to create the exact circumstances and post-apocalyptic worlds their stories inhabit: what precisely went wrong and how, all the major repercussions that our characters now deal with, and what inherent lessons we all should be able to sense in such a world. In this story, however, we merely had to take a walk in the woods. The details are spotty and vague as to why the world is crumbling (or even to what extent it is), and we never get a wide lens on how humanity is dealing with it.

We do, however, join the protagonist midway through his trials as he stumbles through the woods on a weeks-long journey. It’s not specific exactly which woods we’re in, though it seems consistent with the wilds of British Columbia, and my time in the woods of Minnesota harmonized well as I read. While I expected much more interaction with nature and “man vs. wild” survival challenges (a la Hatchet), the author rightly claims (in his bio) to be even more interested in the interpersonal “man vs. man” going on amid the “man vs. wild.” Every encounter with other humans is either one of compassion and relief, or of tense confrontation. Whole routes are avoided because they come too close to potentially dangerous strangers. Further tribal and territorial conflicts among family push the story to its dangling conclusion, and most of these have actually very little to do with “the forces of nature.” And yet the book is certainly about the forces of nature; more specifically, we truly feel how few steps away we are from our total dependence—and complicated influence—on our natural environment. It’s one thing to be able to avoid hungry wolves or shelter from storms; it’s quite another to ensure that you’ll always have enough game to hunt, or that the tools you’re depending on for your survival will continue to function. Furthermore, whom you survive with—and what for—are essentially human questions we all must ask, even when our worlds aren’t falling apart.

There are a few unique things about this book could be seen as weaknesses by some, such as the ending being open to interpretation rather than explicit (no spoilers, but some could find it unsatisfying or rushed). All the dialogue in the book lacks quotation marks, which is a style choice that some could find confusing, but it ultimately works as you get used to it. The style of prose is mostly short, single-clause sentences that some could find choppy, but which partly serve the urgent, serious and sometimes breathless tone of the story overall. It also may not be exactly what you’re expecting based on the back cover summary (first paragraph above); over half the book happens at the family’s woodland estate, and as such it is not merely a “survival journey” story, but rather involves more complex relational, interpersonal and even procedural themes in how the family functions in their isolation. And overall, I sometimes did wonder (and it is never revealed) exactly what happened to the power grid, and how the rest of the world was coping. So while many of these could be considered strengths and are likely intentional, it’s good to know about them beforehand in case you’re expecting something else.

Overall, this a beautiful and challenging story that questions not only our modern way of life but also our obligations to one another. The setting is both beautiful and wild, and I related more to life in the woods than to most survival stories I’ve read with different settings. The pace is such that I found myself reading twice as much as planned in each sitting, even when chapters didn’t end on traditional cliff-hangers; the urgency and foreboding push you forward even when it seems nothing is progressing. And unlike some far-future, post-apocalyptic dystopias that cross into science-fiction (such as Hunger Games) or stretch believability a bit (such as Handmaid’s Tale), this felt simple, realistic and personal. While it never crosses into preachy, every dystopia has an urgent lesson, and we can feel that urgency throughout the story, whether we’re limping through the woods in the rain or sitting comfortably (for now) in a cabin. How long can we sustain what we know? How much are we willing to change, either to avert disaster or deal with it when it comes? How do we decide whether we should group together in larger communities or form a smaller tribe? When is hostility necessary? Is living to survive good enough, or should we want more?

It seems the author’s answers focus on our short-sighted “for-now” attitude, and whether it will be enough for the future. As such, this novel is certainly “for now,” like few others.

Jon Gill