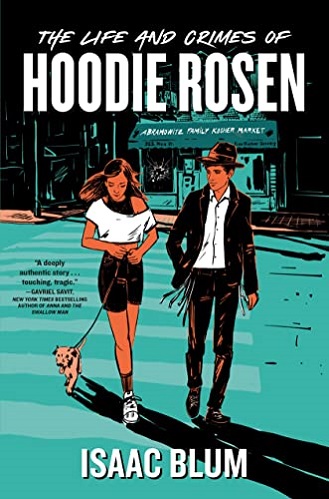

The Chosen meets Darius the Great in this irreverent and timely story of worlds colliding in friendship, betrayal and hatred.

Hoodie Rosen’s life isn’t that bad. Sure, his entire Orthodox Jewish community has just picked up and moved to the quiet, mostly non-Jewish town of Tregaron, but Hoodie’s world hasn’t changed that much. He’s got basketball to play, studies to avoid and a supermarket full of delicious kosher snacks to eat. The people of Tregaron aren’t happy that so many Orthodox Jews are moving in at once, but that’s not Hoodie’s problem.

That is, until he meets and falls for Anna-Marie Diaz-O’Leary—who happens to be the daughter of the headstrong mayor trying to keep Hoodie’s community out of the town. And things only get more complicated when Tregaron is struck by a series of antisemitic crimes that quickly escalate to deadly violence.

As his community turns on him for siding with the enemy, Hoodie finds himself caught between his first love and the only world he’s ever known.

Isaac Blum delivers a wry, witty debut novel about a deeply important and timely subject, in a story of hatred and betrayal—and the friendships we find in the most unexpected places.

Isaac Blum offers a wonderfully sarcastic and yet, at the same time, affectionately personal window into the “life and crimes” of teenage Yehudah (a.k.a. Hoodie) who believes he has found a way to navigate between basketball and his life as an Orthodox Jew. But an encounter with a non-Orthodox girl throws that balance into chaos. The girl, Anna-Marie, is the daughter of the town mayor, a known enemy to Hoodie’s community who is doing everything to keep them from integrating into her preciously non-Jewish town. When the two teenagers are “caught” trying to clean-up anti-Semitic graffiti, Hoodie’s community sees it as an attempt to hide evidence of crimes against them and accuse Hoodie of betrayal, ostracizing him and subjecting him to solitary confinement at his school (yeshiva). But an act of bravery elicits support from the least expected places and opens a path for both communities to find some hope for peaceful coexistence.

What I found most striking about this book is how Blum manages to convey such an endearing and compelling description of Orthodox Judaism through Hoodie’s teenage sarcasm. When describing the strictness of his traditions, for example, he celebrates the fact that he gets to choose the length of his sideburns. But what rings most clear throughout the book is Blum’s sensitivity to the contradictions and complexities of tradition. As Hoodie becomes increasingly ostracized from his community, for example, he describes his traditions as a coat that no longer fits, but a coat that he is still not willing to shed:

“Fit” was the right word. The whole thing was like a jacket that didn’t fit me right anymore. But it was the only one I had. I was naked underneath it. I didn’t really want to wear it, but I couldn’t take it off either, because then what would I have?”

Too often (especially in YA books) we are told to seek our independence and self-expression at all costs, forgetting the importance of what is sometimes left behind or trampled on: family, friends, religion or tradition. But Blum does not suggest as an alternative the adherence to a tradition that is empty, impersonal and unchanging. When Hoodie was at his darkest moment, alone and in the hospital, he found himself praying the traditional Kaddish, finding comfort in an old prayer (although not in the “proper” way since he was not praying with another person). “Meaning,” he realized, “didn’t have to come from someone else’s religious teachings. It was something I could find in myself.”

This book is essential reading for anyone who finds themselves lost between religious or family commitments and personal choice and struggling to find a way to discover new meaning in old traditions. And it is even more essential for anyone who scoffs at others for their traditions and who expects to find meaning in a spiritless vacuum of self-expression and consumerism.

-James Steeves